Globally, 2023 has been an eventful year for banking thus far, with four large bank failures precipitating a loss of confidence in the banking sector. The failure of First Republic Bank marks the latest fallout from the banking industry turmoil that started in March of this year. The troubles began with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, followed shortly after by the seizure of Signature Bank by federal regulators. Unlike the global financial crisis during 2007-2008, which was primarily driven by the significant credit losses that banks and other financial institutions suffered, the recent crisis is being attributed to the surge in interest rates as the Federal Reserve manages inflation. This has resulted in large declines in the market value of U.S. Treasury and government-backed securities, which represent significant assets of the U.S. banking system (higher interest rates mean that the same future cash flows from these securities are worth less today). In addition, banks were forced to offer higher interest rates on their deposits to compete with the interest rates available on “safer” assets. Higher deposit costs were expected to cause a contraction in the net interest margins of regional banks, particularly for those banks where loan growth was slowing and older loans had been granted to customers at fixed interest rates when interest rates were much lower. In essence, higher funding costs from deposits were more than offsetting any increase in loan yields on loan books.

As awareness of higher-yielding alternative securities continued to increase, regional banks struggled even more to compete. Given their inability to raise interest rates on the unhedged fixed-rate portion of their loan books, regional banks could not increase interest rates sufficiently on deposits to retain their customers’ money. During the early part of the pandemic, bank deposit franchises were initially supported by a giant liquidity influx. However, less stimulus and quantitative easing, coupled with higher interest rates after the pandemic ended, meant that banks with higher loan-to-deposit ratios and those more sensitive to higher interest rates had significantly less flexibility to manage their balance sheets.

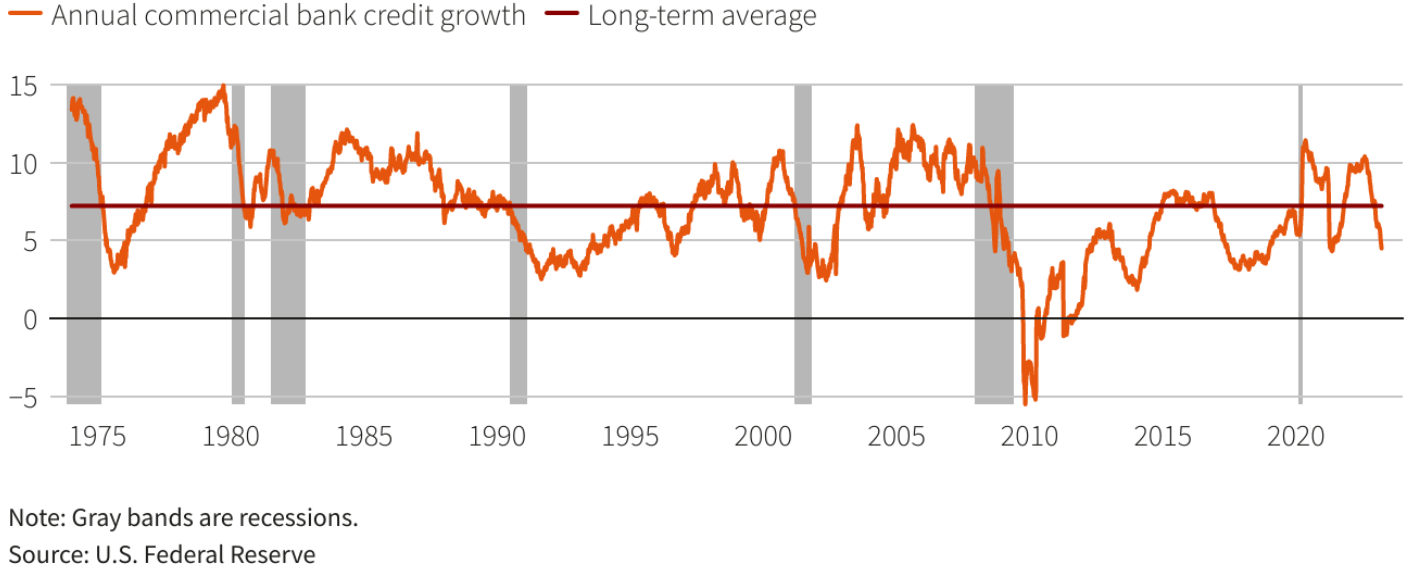

However, with the spotlight on deposits and the problems that banks face in retaining their customers’ deposits when competing with higher interest rate alternative investments, insufficient focus has been placed on another important factor in this narrative, namely loan growth. The financial panic, tightened lending standards, and an increased need to stockpile highly liquid investments curtailed the flow of credit and created an even bigger headwind for the banks than the struggle to retain deposits. Importantly, the flow of credit from banks represents one of the two major sources of new money supply in an economy (the other being the central bank). As the chart below shows, the combination of the factors discussed above has caused banks to be more cautious. Bank credit growth has dropped below the long-term average, and at a rate of less than 5%, the current rate of commercial credit growth is at a level that is often (although not always) associated with an economic recession. Overall, the data therefore suggests that we should expect reduced economic activity in the U.S., potentially with a steep contraction in GDP in the near future.

The response (or lack thereof) from governments to the present crisis reflects a clear divergence in the approach between those banks deemed to be “Globally Systemically Important Banks” and “other” banks. Thus far, the U.S. Treasury Secretary has remained relatively non-committal about issuing a broad or system-wide protection of deposit accounts above $250 000, which some have advocated as one possible solution to the current problems in the U.S. banking sector. However, one thing that has become evident from recent events is that a two-tiered banking system is ineffective, with the inevitable outcome of this murky regulatory picture bringing further consolidation among banks, particularly in the United States. The regulatory approach that has been applied to the bigger banks has made these institutions more resilient and diversified, with the bigger banks becoming part of the regulatory response to provide broader financial stability. In effect, it has become a competitive advantage for a bank to be deemed systemically important.

From a local perspective, the South African banking sector is well positioned and unlikely to face similar hurdles. Firstly, South African interest rates have remained higher than developed market interest rates in all the years since the global financial crisis, and as quantitative easing was never required in South Africa, local banks were less addicted to easy liquidity coming into 2023 than their global counterparts. Secondly, local banks’ balance sheet risk management teams have enhanced their resilience by substantially building up capital and liquidity buffers since the global financial crisis. The adoption of the Basel framework and increased use of stress testing since the financial crisis (by both banks and regulators) also supports banking resilience and stable credit flows throughout the cycle. Finally, the most important South African banks are well-established banks with more stable funding sources, safer and less complex assets, and fewer fixed-rate loans than their global counterparts. In combination, we believe that these factors should ensure that the South African banking sector remains relatively insulated from the current banking turmoil.