On 27 September 2023, South Africa’s minister of Water and Sanitation called on water service authorities to implement water-shifting in order to address the water crisis which had left residents in parts of Johannesburg without water for over two weeks. It is already a well-known fact that South Africa is a water scarce country with a mean precipitation of 497mm/year, more than 40% lower than the global average of 860mm/year. Therefore, any deterioration in infrastructure and/or management capabilities concerning water should never be taken lightly. In 2023, food producers such as Astral and Tiger Brands had announced sizeable investments into initiatives related to water security as the resource plays a crucial role throughout the value chain.

Regarding the recent water-shedding, Minister Mchunu stated that this was due to the power failure experienced at Rand Water’s Zuikerbosch Water Treatment Plant. Though this may be true, the recent figures coming out of the department’s Blue Drop report published last month paint a serious picture for the country’s water security, with power failures having little involvement. The Blue Drop report (published on 5 December 2023 by the Department of Water and Sanitation) provides an assessment of drinking water quality and the extent of water losses (mainly through leaks) for all municipalities in the country.

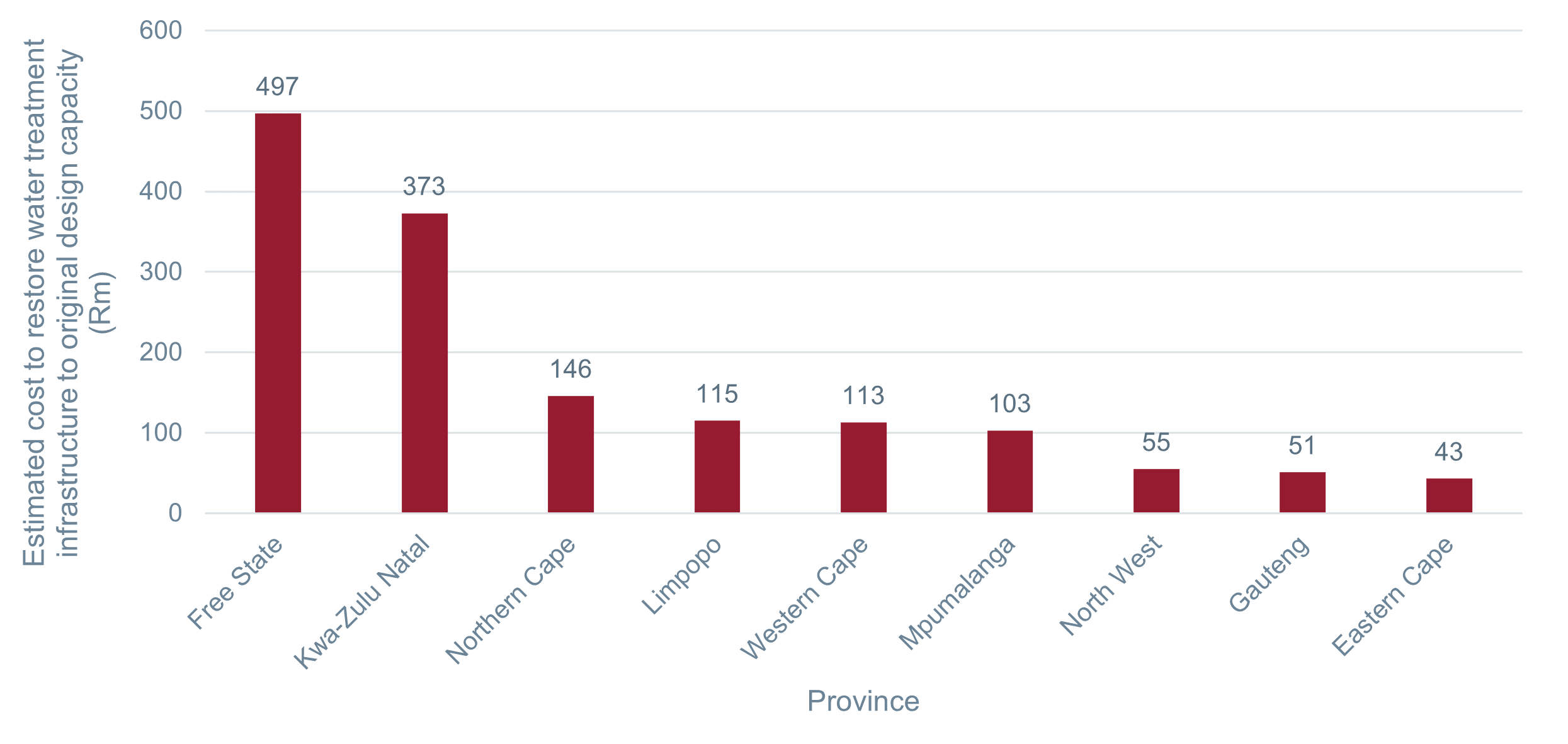

Results from the report show that although drinking water quality is generally good in major metropolitan areas, there has been a deterioration in overall water quality since 2014. The findings reveal that 66% of wastewater treatment facilities fall within the high or critical risk categories, while 47% of drinking water systems exhibit poor or critical levels of performance. The net effect of this is that 46% of water systems pump out “treated” water that is considered microbiologically unsafe and could cause waterborne diseases such as cholera. One of the biggest possible reasons for this performance, according to DWS director general Dr Sean Phillips is a lack of skilled staff and/or a lack of proper process controls. A more obvious factor is the lack of infrastructure investment over the years. The below chart shows the estimated investment per province required to restore water treatment infrastructure to its original design capacity.

Non-Revenue Water

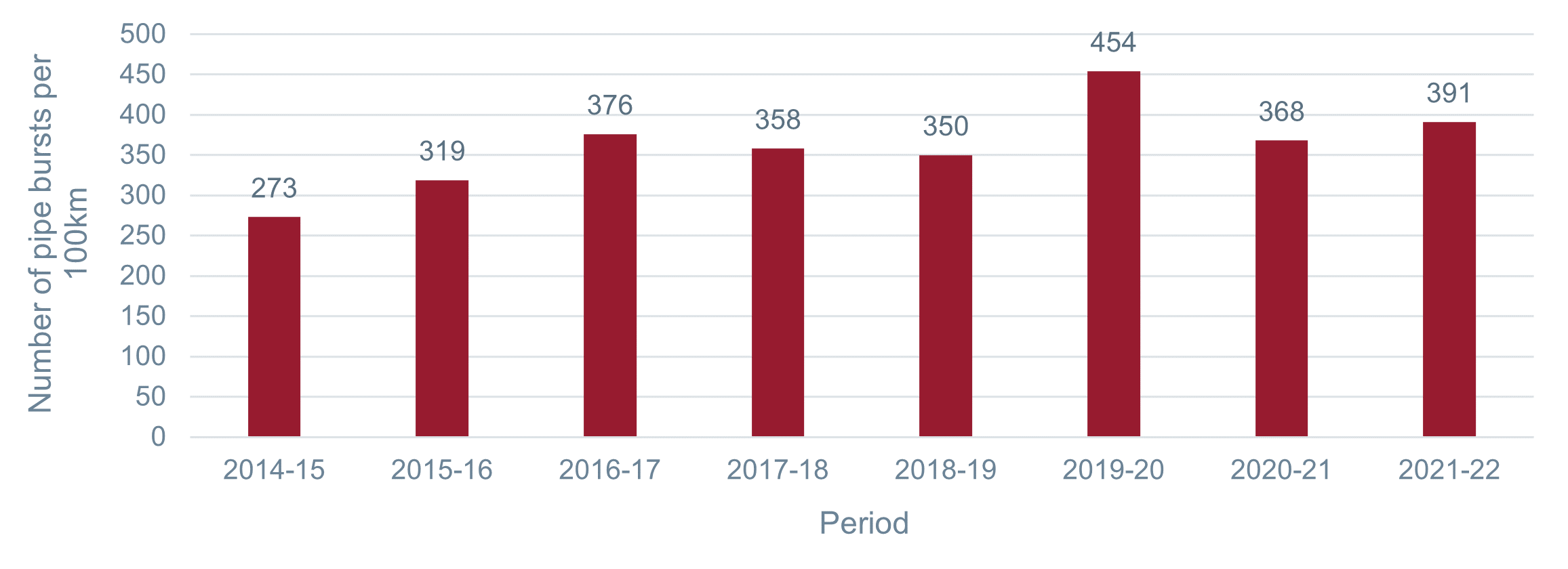

Non-revenue water is water that is “lost” before it reaches the end customer. Losses can be real losses through leaks or apparent losses through metering inaccuracies or theft. Findings from the report show that out of the 4.4-billion cubic metres of water treated for municipal consumption per year, 47% is classified as non-revenue water (global standards guide for a maximum of 15%). Below is an illustration of the number of pipe bursts per 100km as reported by Johannesburg Water over the years.

In the 2019 release of a national water plan, it was indicated that an investment of R900 billion is necessary for water supply and storage infrastructure by 2030. Despite the availability of capital from the private sector, the implementation of such investments hinges on the establishment of effective governance structures. Ensuring that funds are safeguarded against misappropriation and are exclusively allocated to water infrastructure projects is imperative.

To address this challenge, the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) and the Department of Water and Sanitation have collaboratively established a Water Partnership Office. This office serves as a facilitating entity, aiming to streamline and encourage private investment specifically directed towards water infrastructure projects.

The water crisis in South Africa demands urgent attention. Experts warn that if the alarming trend of water service deterioration persists, with the percentage of unsafe water skyrocketing from 5% in 2014 to a staggering 46% today, a bleak future awaits.